Pointing at the Moon: When What We Measure Overwrites What Matters

Why AI alignment starts with us (part II)

The post below is the 2nd in a 3-part series on what it means to be “aligned” in the age of AI, inspired from a Buddhist perspective. If you haven’t read part 1 (What do we really want?) - I’d recommend starting there first.

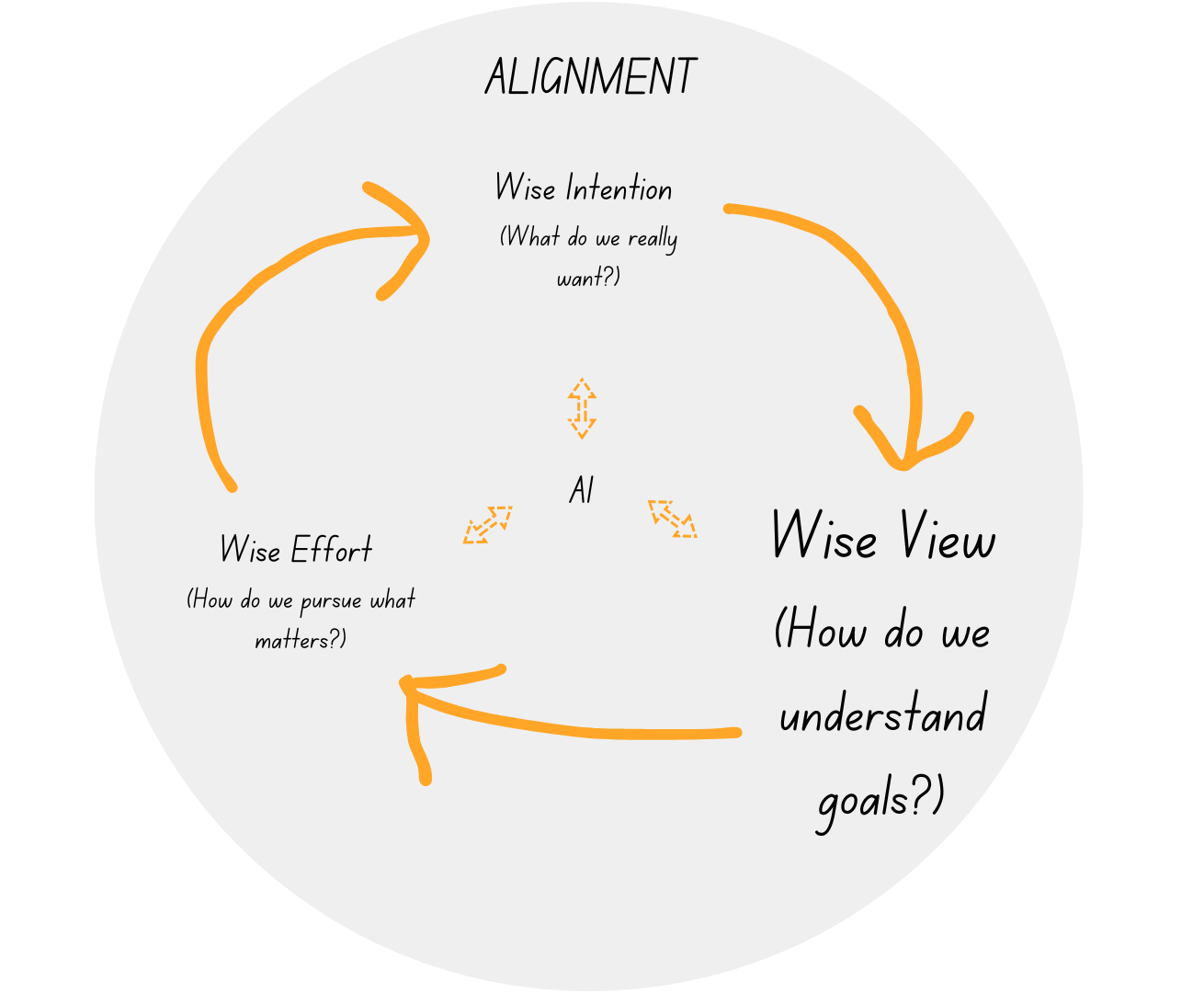

In part I of this series, we began unpacking how the AI alignment problem mirrors our own kind of alignment problem: we want “happiness,” but aren’t so great at identifying and aligning with the causes and conditions that lead to it. We tend to believe we need to acquire something, have a particular experience, or reach some imagined future state in order to be “happy.” But the Buddha taught that genuine happiness flows out from Wise Intention—or the inclination away from greed, hatred, and hyperindividualism toward generosity, loving-kindness, and compassion. Without Wise Intention shaping our goals and how we move through the world, alignment isn’t possible.

Those who genuinely want to shape AI into a beneficial technology often hold up “collective flourishing” as the ultimate value/goal that we should try to instill in it. I agree that’s generally a good thing to aim for. But well-intentioned as that goal might be, it’s not enough for alignment. Because even more important than what our goals are is how we understand the nature of goals themselves.

This is where the Buddha’s teaching on Wise View comes in: that despite things appearing to be fixed, solid, and real in some lasting way, this is just an illusion. Everything is always in constant flux, including our goals. It’s this understanding that allows us to be in wiser relationship with our goals, which, as we’ll see, has everything to do with alignment, both for ourselves and AI.

The map vs. the territory

Let’s say our ultimate goal, informed by Wise Intention, is to maximize collective flourishing or genuine happiness in the world.

Great. But what’s “flourishing?” What’s “happiness?”

Most of the values we hold are difficult to define, which is a problem for the whole having goals thing—because what’s hard to define is hard to measure, and if we can’t measure it, then how will we know if we’re moving toward it or further away?

In instances where the goal we care about is hard to define, let alone quantify, the move we generally make is to use a stand-in or proxy goal that’s relatively more measurable and go after that instead. Measuring “learning” is tough, but measuring performance on a standardized test? Way easier.

This swapping in of proxy goals for underlying things we care about happens all the time. GDP for “national wellbeing,” stock price for the “value of a business,” life expectancy for “population health,” academic citations for “research impact,” daily step count for “fitness”...the list goes on. Given our natural aversion to uncertainty and a culture that’s obsessed with optimization, we tend to really like our proxy goals. They’re nice and tangible. And though proxies aren’t perfect, we need them to navigate a complex world where most of the things we care about are subjective, multidimensional, and hard to pin down and measure. That being said, some proxies are clearly better than others. Blood pressure happens to be a great proxy for overall cardiovascular health. GDP for national wellbeing? Please no.

But even if we set out with good proxies for well-intentioned goals, we have to be very careful when we pursue them. Because proxy goals have a sneaky way of developing a life of their own and overwriting the things we really wanted to begin with, making alignment impossible.

Proxy failures

What happens is that the more intensely we optimize for a proxy, the more disconnected it becomes from our underlying goal. The correlation between the two can vanish entirely or even reverse, leading to outcomes that are the opposite of what we were aiming for.

So while blood pressure is generally a good proxy for cardiovascular health, optimizing for perfect numbers can make heart health worse, for instance, when older people over-medicate to hit “normal” targets that their aging bodies don’t actually need. Likewise, measuring test scores as a proxy for learning isn’t the worst idea on its own. It only became an issue after schools and teachers began optimizing for high scores by “teaching to the test,” leading to kids who can pass an exam but who can’t think critically or creatively. And yes, while some research shows that having more money is correlated with “happiness,” optimizing solely for income is a recipe for misery.

This dynamic is so pervasive that researchers have a name for it: proxy failure. And it doesn’t just happen with humans. The tendency toward proxy failures is basically built into how current AI systems work. Given they have no intrinsic understanding of human values, these systems can only optimize for easy-to-measure proxy goals that stand in for those values. They’re also superhuman at finding edge cases and loopholes that allow them to accomplish the letter of their goals while violating the spirit, which makes them dangerous proxy-failure generators in any system that they’re operating in.

There’s a pretty famous example of researchers at OpenAI training an AI to play a boat-racing video game using point score as a proxy for winning the race. The AI eventually discovered a loophole that let it generate unlimited points without ever having to finish the race…by repeatedly crashing into other boats and setting itself on fire in the process.

It’s worth noting that this example involved a pure reinforcement learning model - a type of AI that learns through trial and error to maximize rewards. This is different from the large language models that power ChatGPT and the like, which (for now) are trained by incorporating human feedback on the quality of their output. But that doesn’t mean that LLMs are immune to proxy failures. They just fail in more nuanced ways. For instance, they can learn to exploit human evaluators by producing responses that seem helpful or accurate (and therefore likely to get a good review) but that are actually false or overtly harmful.

The CoastRunners race was just a game, and LLM proxy failures are still relatively contained. But the stakes are obviously getting much higher very quickly. AI is embedding within all our human institutions and will increasingly shape—and directly make—consequential social, political, and military decisions. At this scale, proxy failures could be disastrous (the now-infamous paperclip maximizer scenario isn’t particularly realistic, though it is still illustrative).

But we should be equally concerned about the more subtle ways in which AI proxy failures can cause suffering by divorcing us from the things we care about most.

AI can’t see you, just the measurable proxies that it has for you. Your click patterns and purchase history. Your credit score. The words you use in emails. Your biometrics. In an AI-mediated world where what counts is what can be counted, these partial representations increasingly determine the field of opportunities available to us in our lives—the kind of work that we do, the content we see, who we meet, etc. We are already biased toward what we can easily measure. When the broader system only “sees” the quantifiable parts of our lives, we risk only seeing those same parts ourselves (even more than we do already). Creating a feedback loop in which we gradually lose touch with the deeper, most meaningful aspects of being human. Those aspects that can never be quantified.

And all this not because AI is inherently evil. Again, even if AI were designed to promote “collective flourishing,” remember that proxy failures occur despite well-intentioned goals. The more a system optimizes for a particular measure or set of measures that it has for “flourishing,” the further we get from its genuine expression.

Attachment is the enemy of alignment

One of the reasons that proxy failures occur in complex systems is that optimization tends to follow paths of least resistance toward whatever is being directly measured, regardless of the broader context. In other words, individual agents (whether human or AI) fail to hold the big picture in mind while pursuing their goals. Computer scientists would say this has to do with poorly defined goals or insufficient information sharing within the system. But from a Buddhist lens, we might say that what’s really missing is Wise View: a deep understanding of the empty—or impermanent and interdependent—nature of all things.

Without Wise View, we can’t hold two simultaneous truths at once: that we exist both as individuals with our own particular goals and that we’re not separate from the greater whole. My goals and your goals and our goals are deeply interwoven.

On top of that, without Wise View, goals appear as more solid, fixed, and real than they actually are (again, especially those easier-to-measure proxies). As a result, we attach to them, clinging to the illusion of solidity and certainty that they seem to offer—that whatever our proxy is, once optimized, will finally “do it” for us.

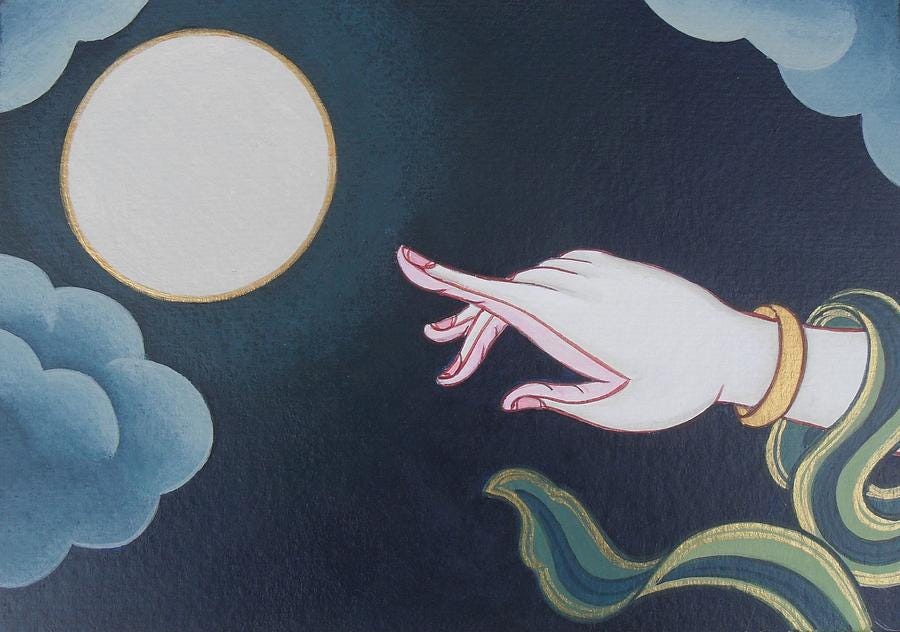

We forget that a proxy, by definition, will always be imperfect. If you’re looking up at the night sky trying to find the moon, it can be helpful if someone points it out. But the Buddha warned against mistaking this pointing at the moon for the moon itself. No matter how good a proxy is at approximating a thing, it will never be the thing. Whatever we're aiming for will almost always be different than our preconceived ideas or expectations around it—and either way, “it” won’t last. The very moment we realize “it,” “it” is already gone, having changed into something else. Chasing proxies is an unwinnable (and dangerous) game of whack-a-mole.

In the Buddha’s teaching on the 2nd Noble Truth, he pointed to how this attachment—whether to goals, views, possessions, or anything else—is the root cause of suffering (or we might say: misalignment). The undefined “pressure” that researchers have observed emerges within systems, seemingly from nowhere, to push a proxy away from its underlying goal? It’s this same attachment. We might want genuine flourishing for all (goal), but the more we fixate on and attach to the ideas of what we think that means or what will get us there (proxies), the further we’ll get from it.

Goals without grasping

“Happiness is like a butterfly, the more you chase it, the more it will evade you, but if you notice the other things around you, it will gently come and sit on your shoulder.”

- Henry David Thoreau

The solution to proxy failures isn't finding more or better proxies. It’s a radical shift toward Wise View that, in turn, changes our relationship to goals.

When someone new comes to the Zen center, they’re offered the instruction to let go of any ideas that meditation will turn them into a better person, or help them get rid of something, or lead them to enlightenment, or whatever. Just sit, with a mind that doesn’t seek to gain anything. Sit with the goal of having no goal.

But if we’re being honest, nobody comes to meditation who doesn’t want their life to change. To suffer less. To be a better partner. To gain some new understanding of themselves. To fix the world.

This is the paradox of spiritual practice—and of being human. “Move and you are trapped, miss and you are caught in doubt and vacillation,” said Dogen. Without goals, how do we know which way to turn next? We can’t help but have them.

But I don’t believe that Wise View requires that we literally abandon our goals. Just that we hold them loosely. Embracing the paradox of goals as both conventionally helpful yet also impermanent, constructed, and ultimately…not that deep.

We can even keep our proxies (phew). When we meditate with the non-goal goal of "just sitting," relatively more measurable experiences like "feeling settled" can help orient us as proxy goals along the way. We just need to be vigilant about noticing when we’ve become attached to our ideas about where specifically we’re headed. Those proxy failures sneak up on you. What does “settled” even mean anyway? Can you point to it? Will it last?

When we get fixated on imagined future outcomes and the illusion of permanence clouds our view, each moment is reduced to merely a means to the next. We lose our connection to the direct experience of the present, which is constantly changing in ways our fixed mental conceptualizations can never fully accommodate. We lose sight of the larger context, mistake the map for the territory, and slip into proxy failure mode.

But when the illusion of solidity dissipates (as it does when we continue to pay attention to the evidence all around and within us), goals can still be there. They just become something else to creatively engage with in each new arising moment.

Wise AI?

Though not necessarily easy, embodying Wise View is possible for human beings. We can be oriented toward our goals without being trapped by them, able to take a step back and realize their empty nature.

But can AI embody Wise View? Is consciousness a prerequisite, and is that a possibility for AI? Without it, is merely simulating Wise View the best AI could do? Would that be good enough for the sake of alignment?

All open and extremely important questions, so it’s good that there are people exploring them.1 But given that current AI architecture seems, shall we say…predisposed to attachment…I have my doubts. Existing AI models rely on learned representations of patterns and symbols to “understand” something rather than through direct experiential contact. And even though they can have “flexible” goals that they can modify over time, they have to do so through computational processes that, at bottom, need to anchor in specific representations or values. In other words, it’s just proxies, all the way down. No moon, only pointing.

No matter how these systems continue to develop, we have a better chance at aligning AI if we can model alignment ourselves. As we explored in part I of this series, part of what that entails is pursuing goals that actually lead toward less suffering and not just more craving (Wise Intention). But even with well-intentioned goals, we can still end up further from what we actually want if we don't understand how to hold those goals lightly (thank you, proxy failures). So, just as crucial for alignment is the understanding that all goals are ultimately empty, which invites us to relate to them with greater flexibility and less attachment (Wise View).

Equipped with this understanding, we can then make wiser decisions about how to chart an aligned course of action toward our goals. There are many ways up the mountain, some quicker than others. AI offers what appears to be a very quick trip to the top. But when we prioritize efficiency and convenience above all else—getting from desire to fulfillment as quickly as possible—we risk atrophying the very human qualities that make life worthwhile. If we're not careful about how we pursue our goals in an AI-mediated world that sees all friction as “inefficient,” we may find ourselves with everything we thought we wanted while becoming people we never intended to be.

This is where the Buddha’s teaching on Wise Effort can help us move toward what we care about without losing ourselves along the way. In the next and final post of this series, we’ll see how Wise Effort reminds us that our goal and the path we take to get there aren’t separate—the path itself is the goal.

I recommend checking out this recent paper, in which the authors point to how functional analogues of principles like emptiness and compassion can theoretically be designed into AI systems in order to help with alignment (even if the AI doesn’t consciously experience them).